The Irish Traditional Music Archive (ITMA) is committed to providing free, universal access to the rich cultural tradition of Irish music, song and dance. If you’re able, we’d love for you to consider a donation. Any level of support will help us preserve and grow this tradition for future generations.

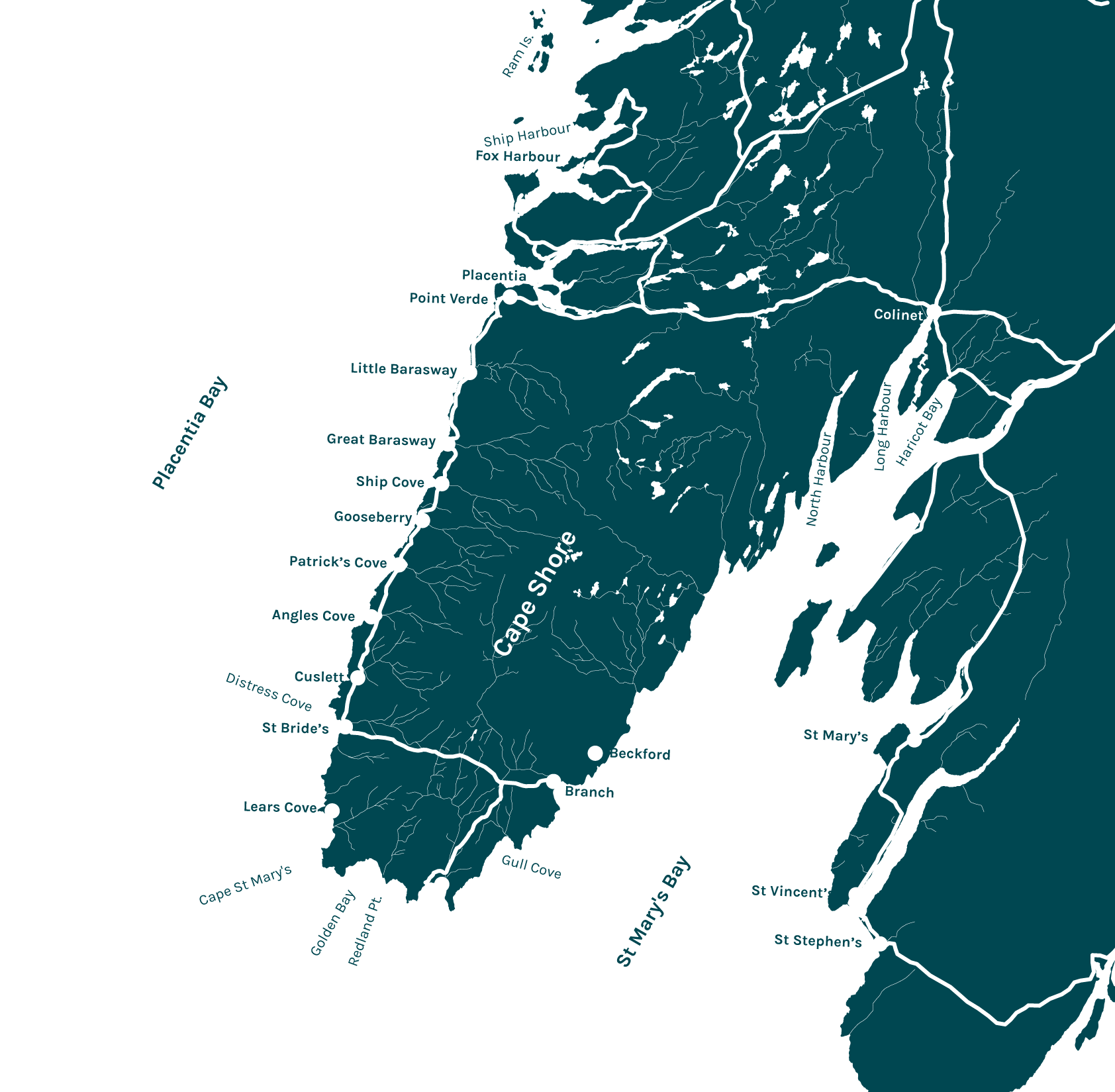

When Aidan O’Hara first visited the Cape Shore in 1975 there was only a single dirt road that dead-ended in Point Lance. Branch, shown in the photograph above, was the penultimate stop on that road (photo courtesy of Aidan O’Hara; used with permission).

Caroline Brennan—or, Aunt Carrie as she was affectionately known—of Ship Cove was one of the first people whom Aidan O’Hara met when he visited the Cape Shore in October 1975. The Brennan household was a frequent stopover for people travelling to Placentia from Branch, Point Lance, and all along the Cape Shore. Frequent visits meant that there was always a story being told and a song or two being sung. It was a natural place for Aidan O’Hara to begin learning about the old songs, stories, and the history of the community.

Caroline Brennan had a vast store of songs and stories. Some of those songs told of tragedies.

Others told of romance in a bygone era.

And some songs were purely for fun.

Commenting on Caroline Brennan’s version of “The scolding wife,” Virginia Preston Ryan notes that the songs served particular purposes. Lives working in the fisheries and farms of the Cape Shore were often hard and came with their fair share of tragedies. These hardships were reflected in the serious songs of many singers. But comic songs and ditties also had a purpose.

They remind everyone that life must not be taken too seriously. They reintegrate people in the present. They get everyone laughing, clapping, and tapping their feet, and provide the needed release from the sober thought and heavy concentration induced by a song of homesickness or of loss-at-sea. One such ‘silly song’ tends to lead to another. But they eventually pave the way for another slow song or ballad and composure is restored.

Between 1975 and 1978, Aidan O’Hara spent countless hours in the company of Caroline Brennan, listening to her sing, but also learning about the history of the Cape Shore. She told him about superstitions and described the many ways in which Irish sayings and customs remained integral parts of life on the Cape Shore.

During an early visit to Caroline Brennan, her niece Rita and nephew-in-law Dermot Roche called in. This was the beginning of Aidan O’Hara’s life-long friendship with the Roche family. On each subsequent visit to the Cape Shore, Aidan—and sometimes his wife Joyce and their children—stayed with the Roche family in Branch.

Dermot’s home was the place where Aidan O’Hara and his family stayed whenever they came to visit Branch. Though only a child at the time, Karen Sarro (née Roche), one of Dermot and Rita Roche’s children, recalls vividly the house parties, visits from an older generation, and the significance of the O’Haras’ visits to the community.

Aidan’s visits were always filled with fun—the music, the songs, the dancing, but also the laughter—it was a special time that we looked forward to. The older folks took pride in their knowledge of the past and were so happy reliving the moments and the telling of the old stories as well as recitations. It was a magical time that brought the community closer and gave us pride in our traditions.

Aidan O’Hara’s visits to Branch were always occasions for a “time”: neighbours called over, songs were shared, and the music and dancing went on until the wee hours of the morning.

The majority of Aidan’s recording happened in the informal context of a “time.” The lively conviviality of such occasions was captured on film when Aidan returned to the Cape Shore a few years later with a Radharc production team. The opening scene from the 1981 documentary The Forgotten Irish features John Joe and Monica English, John and Helen Hennessy, Leo English and Rita Roche, and others dancing a set in the Roche family kitchen.

Gerald Campbell was a popular guest at parties because of his skill on the accordion—“cardeen” in local parlance—and the harmonica. But the older generation knew how to make due in the absence of instruments. Mouth or “gob” music was a popular substitute when musicians were scarce. Patsy and Bride Judge of Patrick’s Cove, another community on the Cape Shore, describe some of the popular tunes from the area. They also detail when each tune was likely to be heard in a set.

While set dancing got everyone up on their feet, certain individuals were known for their facility as solo step dancers. John Hennessy of Branch demonstrates a few steps while Gerald Campbell accompanies on the harmonica in another scene from The Forgotten Irish.

This style of step dancing may have been handed down from dance masters active during the 19th century in Newfoundland. Mick Nash, a man from Branch who was in his 90s, told Aidan O’Hara about a dancing competition between two dance masters that happened in Angel’s Cove, a small community on the shore of Placentia Bay. One of the dancers had different steps for each minute of a 45 minute stretch. The other master was so light-footed that he could dance on the bottom of a plate.

Song, though, was really the centre point of parties. One of the reasons Aidan and Joyce O’Hara found such a warm welcome in the communities of the Cape Shore was that they were folk singers with fine voices, eager to listen but also willing to share a song or two themselves. When Aidan brought out his Uher 4000 report reel-to-reel tape machine and set up a microphone, he wasn’t just taking songs from the Newfoundlanders who welcomed him; he was also contributing to the joy and vitality of local traditions.

All of the singers had their own party piece, so to speak. If Jack Mooney was present, for example, no one else would sing “The Irish colleen.” That was his song.

Ellen Emma Power’s song was “Just before the battle, mother.”

Gerald Campbell knew many songs, but perhaps was best known for his rendition of “The girl who slighted me.”

Henry Campbell, Gerald’s father, was mentioned by many of the singers whom Aidan O’Hara recorded as the person who had the words for long ballads that the old people of the Cape Shore sang. These included songs about shipwrecks, songs about going to war, but also ditties and long romances.

The Roche’s home in Branch was Aidan’s base when he visited the Cape Shore, but from there he travelled around. He called into the homes of friends, neighbours, and relatives who were known to sing or share a story or two. That’s how he came to know Tom and Minnie Murphy of St Bride’s.

Tom Murphy’s family were all known as good singers. It’s less clear where Minnie Murphy learned her songs. They just came easily to her when she was a young women.

I could hear a song three or four times and then would just know it.

During visits in April and May 1976, Tom Murphy sang “The broken-hearted milkman,” a light-hearted song about a fickle woman.

Minnie Murphy sang a song with a much more serious subject, “Down by the Riverside.” The song tells of an ill-fated marriage and a man who hangs in Wexford Gaol after murdering his wife.

With the exception of an occasional come-all-ye, traditional singing in Newfoundland is typically a solo endeavour. However, Tom and Minnie Murphy enjoyed singing together.

Rather than singing in unison, Tom and Minnie performed in parallel harmony—in a series of open 4ths and 5ths. Where they learned this approach remains unclear. Perhaps a clue lies in another recording of “The bonnie bunch of roses” by Cyril and Helen Whelan of Red Island, Placentia Bay. Collected by Eric West, in this recording the singers stop at the end of the first verse and Cyril comments that the problem of men and women singing together is that the key rarely suits both. Tom and Minnie Murphy may have developed their open harmonies as a way of avoiding this problem.

Reflecting back on his time spent on the Cape Shore, Aidan O’Hara recalls the excitement of parties and the serendipitous meetings that resulted in quieter visits with individuals. Watch an interview with Aidan O’Hara in which he describes the people he recorded and occasions for recording. Becoming a collector, he emphasises, was the accidental result of “a most disorganised affair.”

Retrace Aidan O’Hara’s travels around the Cape Shore and meet the singers who generously allowed themselves to be recorded. Explore the galleries, playlist, and songsheets of A Grand Time to learn more about the unique traditions of the Cape Shore.